Coca-Cola Case: What Every Tax Professional Should Know

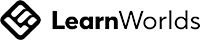

Discover the essential concepts of TP in one concise, easy-to-follow cheat sheet.

Get your free TP cheat sheet!

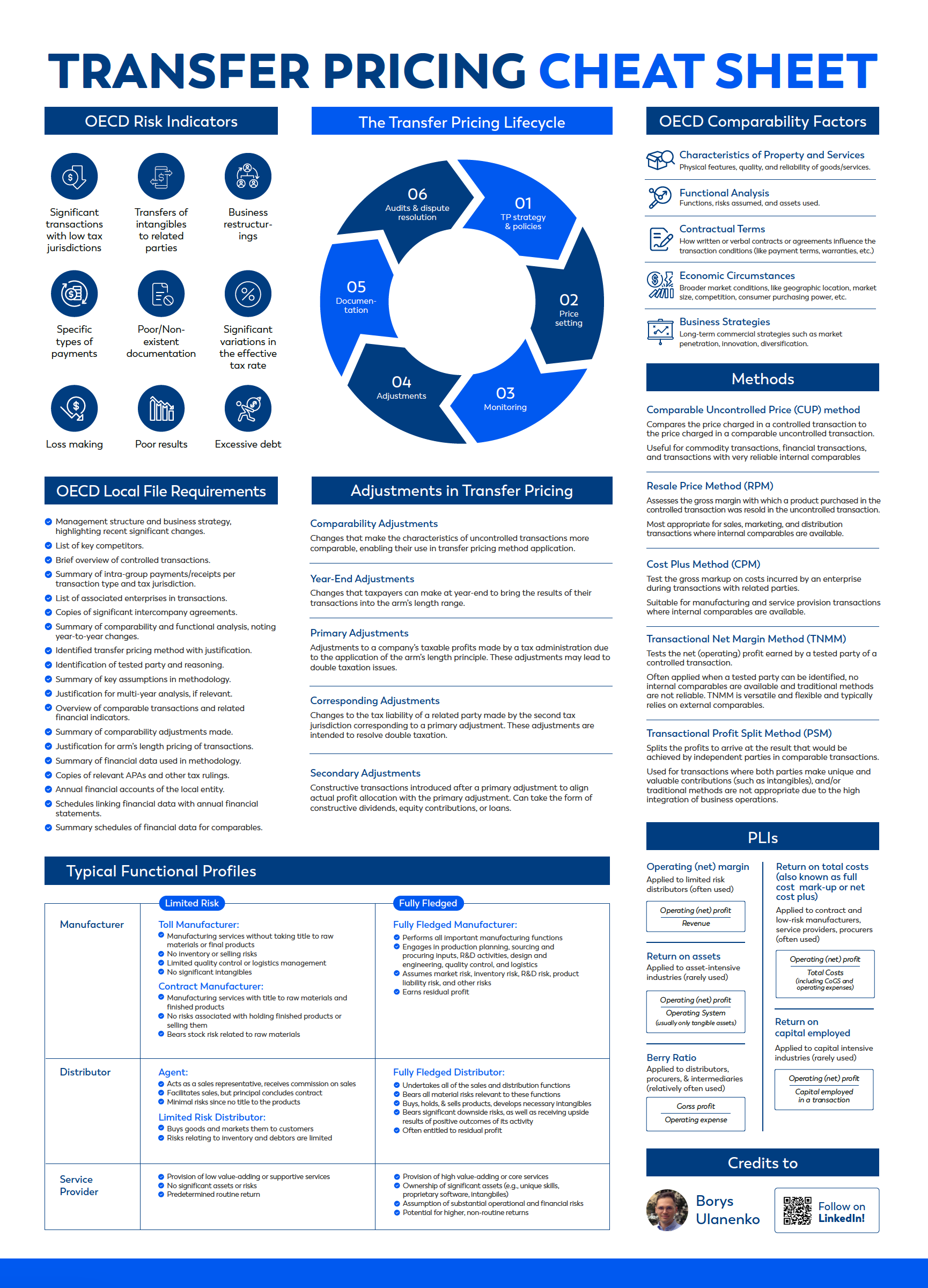

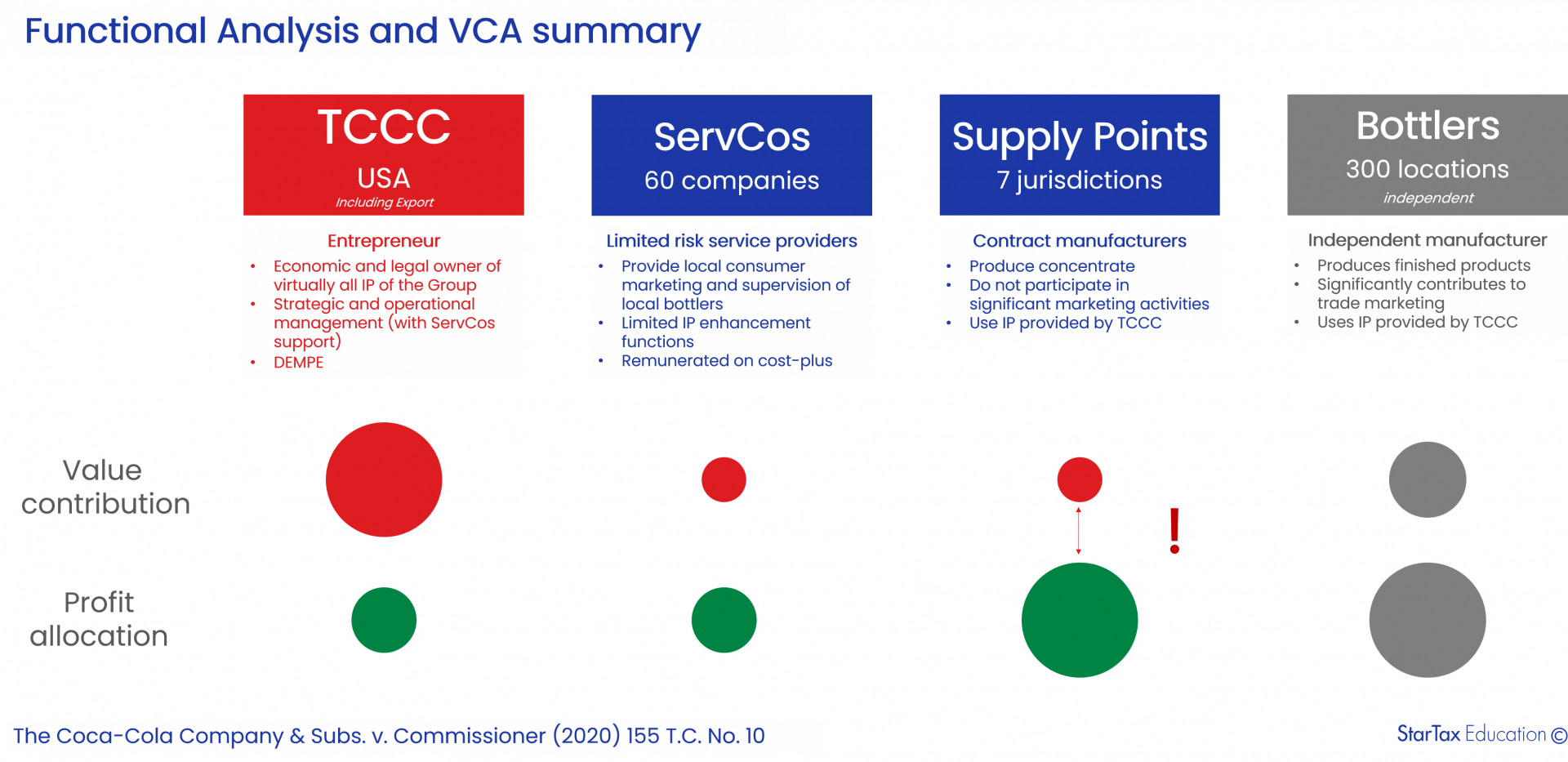

- Supply Points – Coca-Cola subsidiaries that

manufacture and supply concentrate to local bottlers. In the past, there were

dozens of supply points around the world, but then gradually consolidated

manufacturing of concentrate in 7 supply points located in Chile, Ireland,

Brazil, Egypt, Costa Rica, Swaziland. Supply points are primarily responsible

for concentrate manufacturing, while their role in marketing and advertisement

was minimal. TCCC provided Supply Points with manufacturing technologies,

recipies, know-how and other valuable IP.

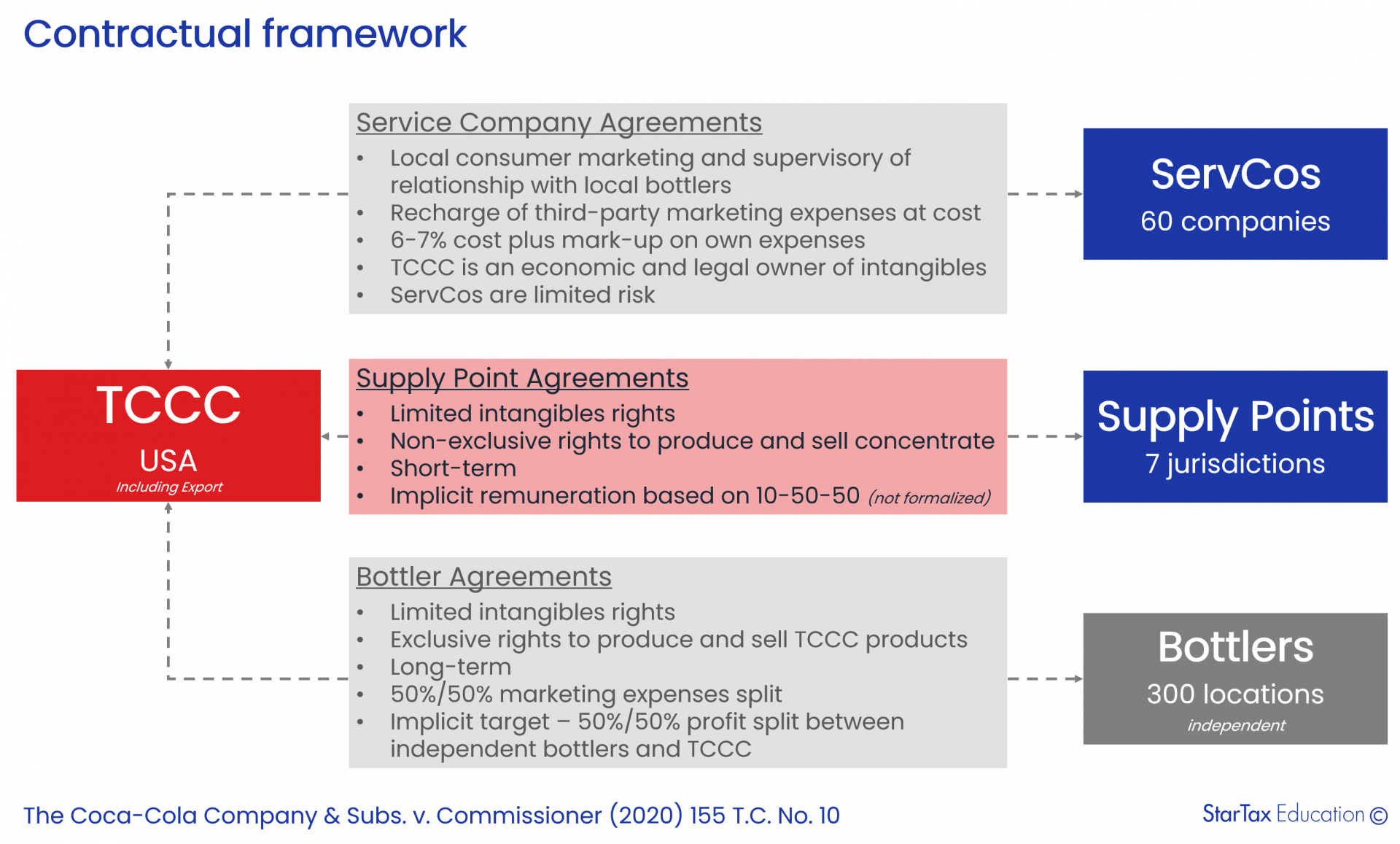

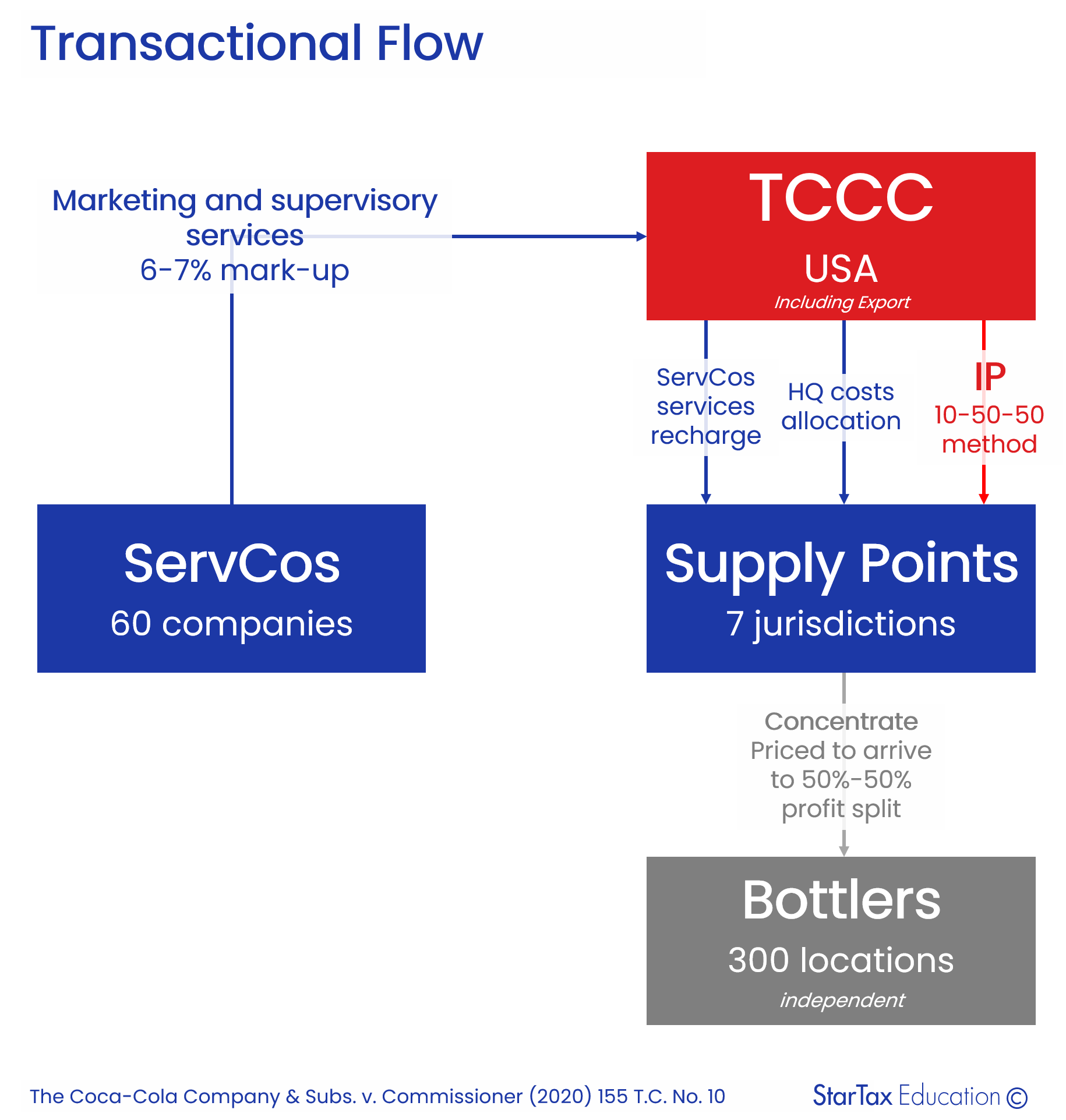

- Service

Companies (ServCos)

– around 60 subsidiaries, each serving one or more national markets. ServCos were

responsible for local advertising and in-country consumer marketing activities, which they

carried out with assistance from third-party media companies and creative

design firms. The ServCos were also responsible for liaison with local

bottlers, a function petitioner called “franchise leadership.” A few ServCos

had research and development (R&D) centres, which served multiple national

markets. ServCos played an important role in Coca Cola trademarks enhancement.

- Bottlers – independent Coca-Cola bottlers that produce the vast bulk of the Coca-Cola beverages. The bottlers produced most of these beverages using concentrate manufactured by the supply points. As appropriate to the particular drink, the bottlers mixed the concentrate with purified water, carbon dioxide, sweeteners, and/or flavorings; injected the finished beverages into bottles and cans of various serving sizes; packaged and warehoused these items pending distribution; and delivered the beverages to retail establishments that included supermarkets, small retail stores, bars, and restaurants. Bottlers were contributing significantly to trade marketing and distribution.

Contractual

framework, transactions under review and dispute points

TCCC and

Supply Points entered into Supply Point Agreements, which granted the Supply Points

the rights to produce and sell concentrate in accordance with TCCC’s

specifications. The profit from concentrate sold by Supply Points to Bottlers

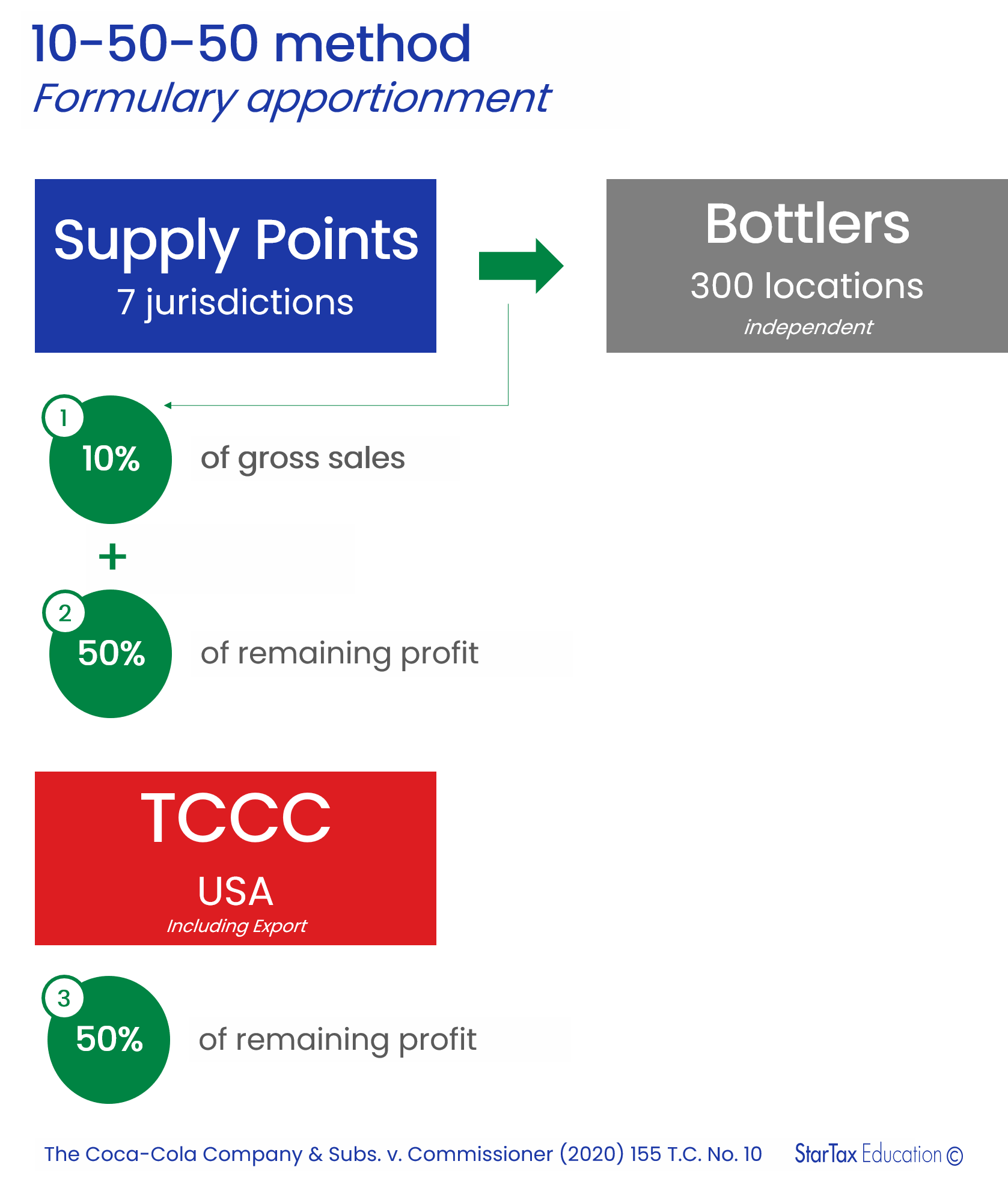

was split between Supply Points and TCCC based on “10-50-50 method.” This was a

formulary apportionment method to TCCC, and the IRS had agreed in 1996 when resolving

tax liabilities of Coca-Cola for 1987-1995. This method permitted Supply Points

to retain profit equal to 10% of their gross sales, with the remaining profit

being split 50%-50% with TCCC. Supply Points paid 50% profit split to TCCC in the

form of royalty (with an option to remit dividends instead).

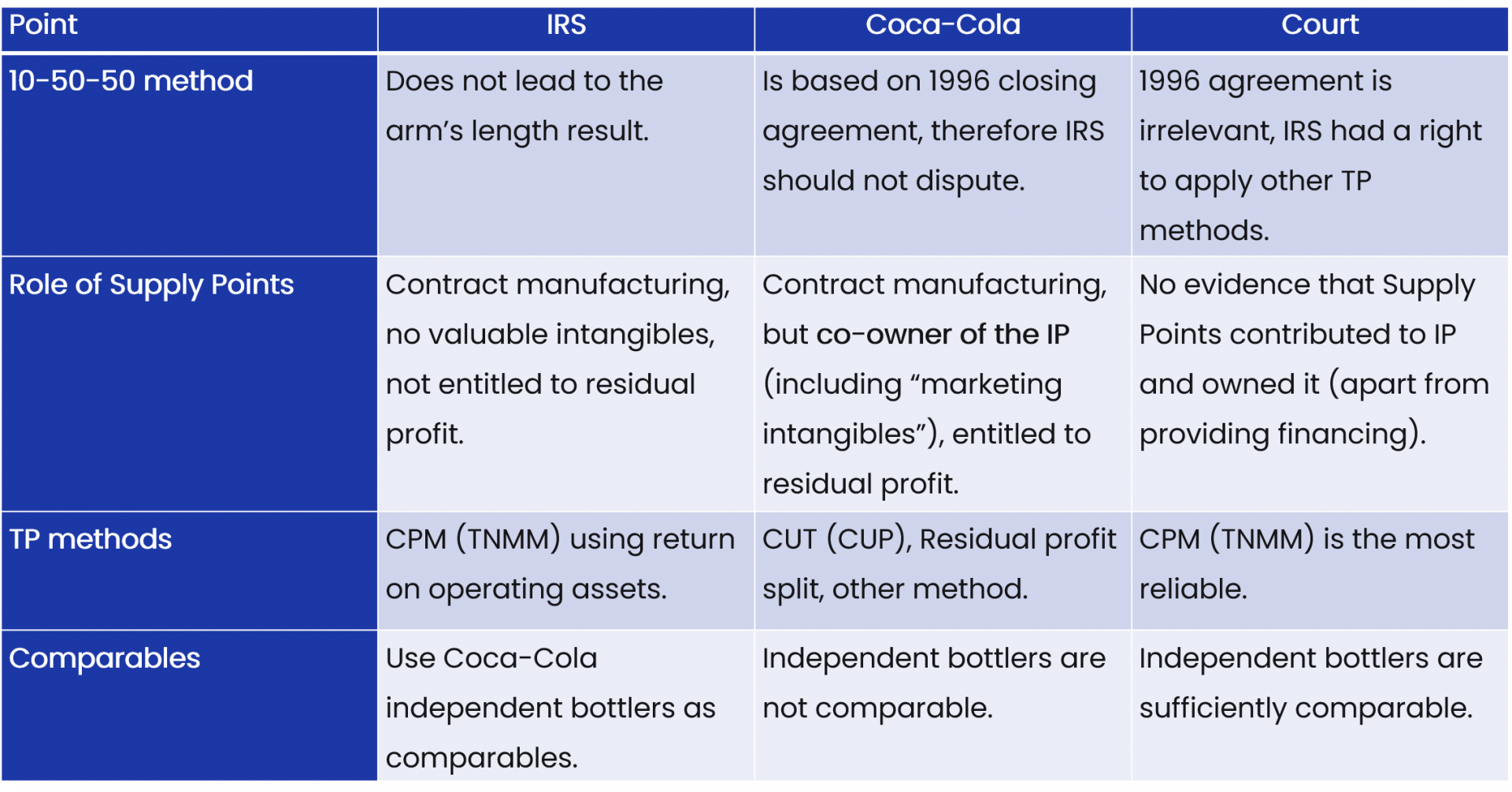

When auditing 2007-2009, IRS disagreed with 10-50-50 method, as it did not lead to the arm’s length result and overcompensated Supply Points. From the financial data disclosed in the case, it is evident that supply points were receiving a major part of the group profits. Perhaps not accidentally, a weighted average income tax rate of Supply Points was only 6.3%.In the case, IRS disagreed with 10-50-50 method, as it did not lead to the arm’s length result and overcompensated Supply Points. From the financial data disclosed in the case, it is evident that supply points were receiving a major part of the group profits. Perhaps not accidentally, a weighted average income tax rate of Supply Points was only 6.3%, which is in line with routine return expected from such companies. IRS applied the comparable profits method (TNMM in OECD) and tested Supply Points as contract manufacturers with no material intangible assets involved.

Positions

and key arguments

Conclusion

Court supported the IRS in all material aspects of the case. Essential points highlighted by the decision:

- Functional analysis and actual conduct are key – it is evident that Coca-Cola had issues with inter-company agreements. Essential terms were missing, and the actual conduct of parties was significantly deviating from the contractual framework. In some instances, Coca-Cola was not able to locate intra-group agreements at all. While Coca-Cola witnesses stated that Supply Points contributed to the creation of IP, they were not able to support their statements with facts.

- When comparables are more advanced (“complex”) than the tested party, IRS still can use them (if it benefits taxpayer) – Coca-Cola tried to challenge the CPM (TNMM) application by stating that independent bottlers (uncontrolled transactions) were not comparable. The Court agreed that in some instances, bottlers played a more important role (i.e., contributed to the IP development). However, it means that using them as comparables is conservative and will benefit Coca-Cola (and not IRS), as less taxable income will be reallocated to the US (and not more).

- Taxpayers are not allowed to disregard their own contractual framework – Coca-Cola tried to insist that even though the contractual framework did not provide for IP ownership to Supply Points, in economic substance, Supply Points still were economic co-owners of the IP. The Court rejected the argument, stating that the US regulations only allow IRS to disregard contractual relationship, and taxpayers should stick to their own agreements.

- Funding does not lead to the IP ownership – TCCC recharged some ServCos marketing expenses and other costs to Supply Points. The Court highlighted the fact that Supply Points were just paying for marketing without actually playing a role in it.

- BEPS, VCA,

OTP and other modern abbreviations – it is evident from the case that structure that Coca Cola employed was

outdated and inadequate for the post-BEPS world. There was an apparent disconnect

between value creation and profits. There were issues with operational transfer

pricing and contractual framework. As a result, in 2020, Coca-Cola was not able

to put forward any strong arguments to challenge the IRS position.

- "Intra-company profit shift" test - IRS (and tax court) compared profitability (return on assets - ROA) of Coca-Cola Supply Points with broad market data, as well as with ROA of the Coca-Cola group as a whole. Obviously, ROA of Supply Points was extreme and the residual profit allocation was not in line with economic returns. This test will not serve as a transfer pricing analysis but can be used as a risk assessment tool by other taxpayers (and/or tax administrations).

There were several other interesting discussion points, and therefore we recommend reading the original case decision in full.

What did you like in this transfer pricing litigation case? Share it with us using contact details below.

For more details about the textbook and the course, contact us:

Featured links

Get your free TP cheat sheet!