Intercompany Loans for State Purposes: Two Illustrations of Debt Push Downs and Pricing

Harold McClure

The

November 2020 DHG webinar entitled “Overview and Considerations for Domestic

Transfer Pricing” considered various tax planning strategies including debt

push downs. Consider a holding company such as Berkshire Hathaway Energy that

incurs third party debt on behalf of its operating affiliates. The holding

company incurs interest expenses, while the operating profits are booked by the

operating affiliates. The debt push down strategy allocates the interest

expense to the operating affiliates.

We illustrate this

strategy as well as the pricing issues for the evaluation of arm’s length

interest rates using both recent financing for Berkshire Hathaway Energy and

the financing of how Amazon acquired Whole Foods.

I. Berkshire Hathaway

Energy

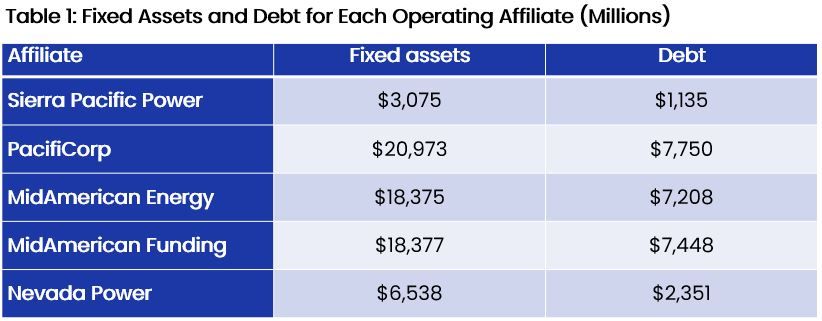

Berkshire Hathaway Energy is a holding company with the following

operating affiliates: PacifiCorp, MidAmerican Energy, MidAmerican Funding,

Nevada Power, and Sierra Pacific. These operating affiliates are regulated

utilities providing energy such as electricity to their customers. These

operating affiliates collectively own approximately $70 billion in fixed

assets, which are financed with over $25 billion in third party debt. Table 1

shows the fixed assets and debt allocated to these operating affiliates as of

December 31, 2019.

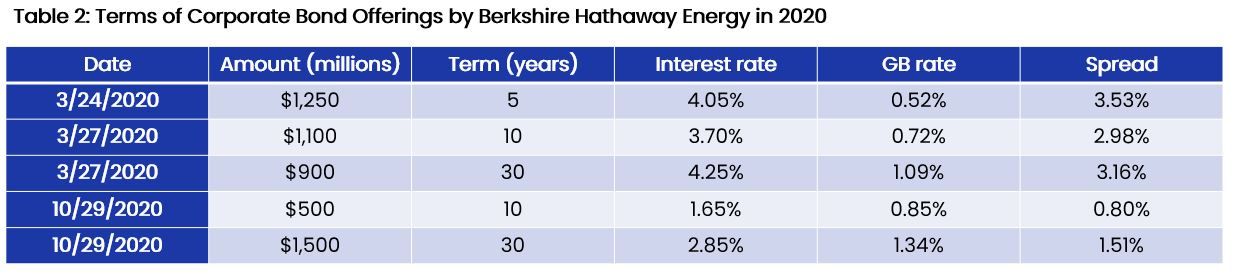

Between May 24, 2020 and October 29, 2020,

Berkshire Hathaway Energy issues $5.25 billion in corporate bonds on various

dates and various terms to maturity. Table 2 summarizes these corporate bond

offerings including the interest rate. While the credit ratings for each

operating affiliate were A, the interest rates on the debt issued in late March

were quite high relative to the corresponding government bond (GB) rate.

A standard model for

evaluating whether an intercompany interest rate is arm's-length can be seen to

have two components — the intercompany contract and the credit rating of the

related party borrower. Properly articulated intercompany contracts stipulate:

· The date of the loan;

·

The currency of denomination;

· The term of the loan; and

· The interest rate.

The

first three items allow the analyst to determine the market interest rate of

the corresponding government bond. This intercompany interest rate minus the

market interest rate of the corresponding government bond can be seen as the

credit spread implied by the intercompany loan contract.

Table

2 calculates the credit spread on each of these corporate bond offerings. Credit

ratings are letter grades, which require translating into a numerical credit

spread. The fallout from the COVID-19 crisis includes volatile credit spreads

almost reaching what we witnessed after the collapse of Lehman Brothers in the

fall of 2008.

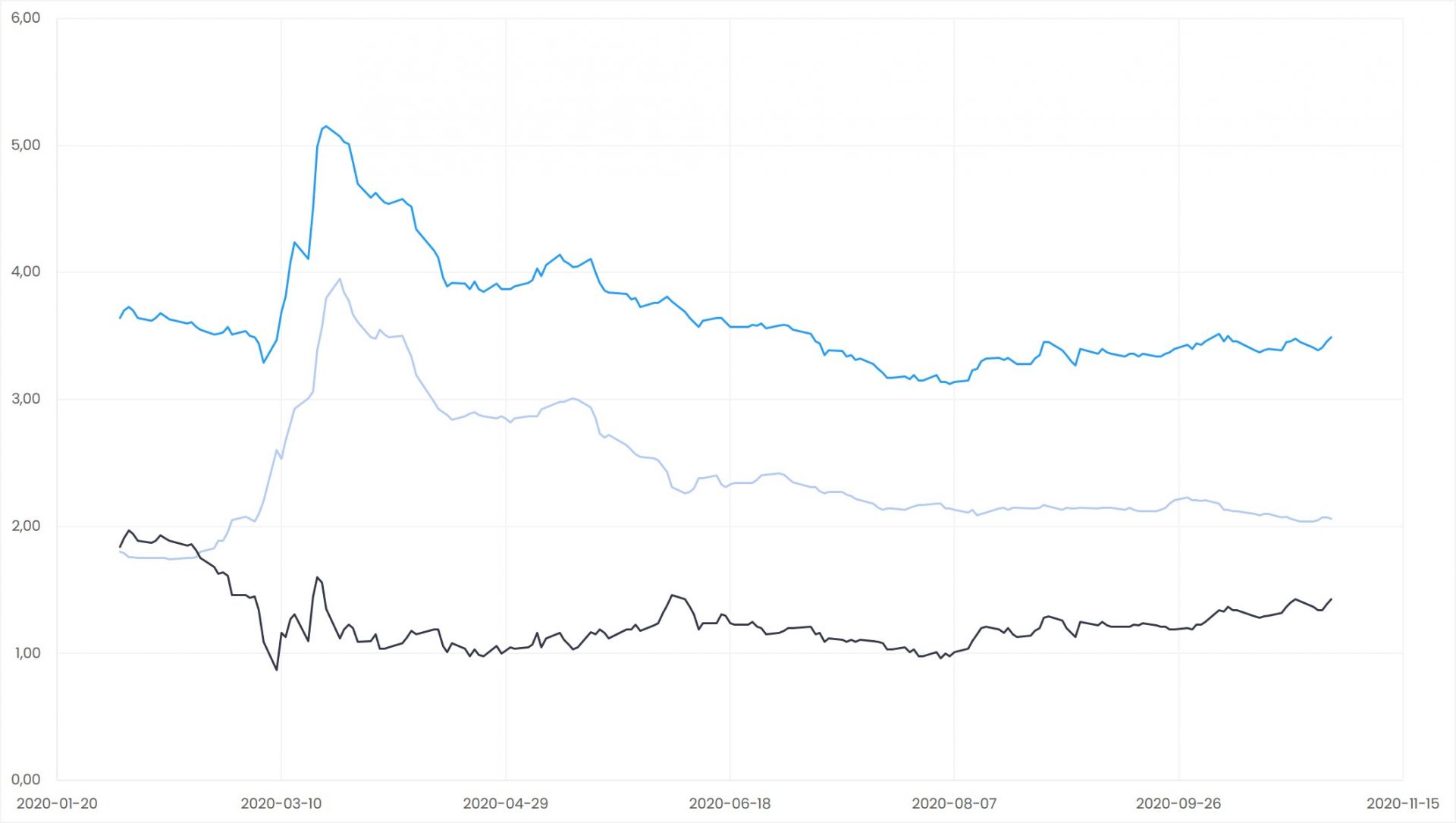

I discussed the spike

in credit spreads during the period after the COVID-19 became evident.[1]

These discussions focused on the difference between the interest rate on

long-term corporate bonds rated BBB and the interest rate on 20-government

bonds. The following figure shows these interest rates and the implied credit

spread from February 3, 2020 to October 30, 2020.

While

the interest rate on long-term government bonds fell from 1.8 percent in early

February to around 1 percent after the recognition of the COVID-19 crisis,

interest rates on long-term corporate debt rose from around 3.6 percent to

around 5 percent. The credit spread on corporate debt rated BBB spiked from around

1.8 percent in early February to near 4 percent as of March 23. This spike in

the credit spread moderated over the rest of 2020 was only 2 percent by the end

of October.

Miguel

Faria-e-Castro, Julian Kozlowski, and Mahdi Ebsim noted this spike in credit

spreads.[2]

The rise in observed credit spreads began on February 28 and peaked on March

23, which was the date that the Federal Reserved announced measures to stem

this financial crisis. These authors cited evidence on credit spreads for

corporate bonds with credit rating A- and better, corporate bonds with credit

ratings between BBB and BB-, and corporate bonds with credit rating B+ and

below. The credit spreads shown in table 2 are consistent with their evidence

on credit spreads for corporate bonds with credit ratings A- and higher.

II. Amazon Acquisition of Whole

Foods

Amazon

purchased Whole Foods during the summer of 2017 for $13.7 billion. This

purchase price represented a premium over the market value of Whole Foods at

the time of the acquisition and was almost twice the book value of Whole Food’s

assets.

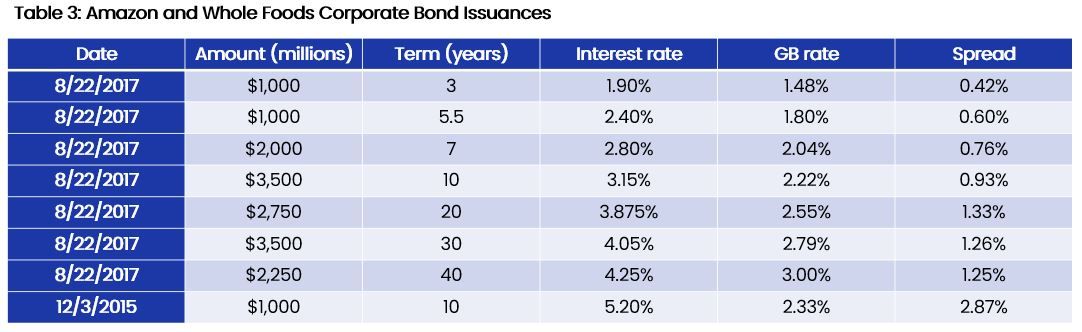

Amazon

also issued $16 billion in corporate bonds on August 22, 2017. Table 3 shows

the key terms of these corporate bond issuances as well as the corresponding

government bond rate for the various terms to maturity. The credit spreads for

these corporate bonds were consistent with a credit rating of A. Some

commentators were surprised that Amazon paid higher credit spreads than other

high technology companies such as Apple. We should note that not all high

technology companies are alike as Apple’s operating margins then to be several

multiples of Amazon’s operating margins.

At

the time of the acquisition Whole Foods had $1 billion in long-term debt from a

corporate bond issuance on December 3, 2015. The terms of this corporate bond

issuance is also shown in table 3 along with the interest rate on 10-year

government bonds on that date. The credit spread was 2.87 percent, which was

consistent with Whole Food’s BB+ credit rating.

If

Amazon wished to push down some of this new financing as of August 22, 2017,

two questions exist. One is how much debt could be pushed down in the form of

intercompany loans from Amazon to its new Whole Foods operating affiliate?

Amazon would not likely prevail in pushing down all $16 billion in debt but an

intercompany loan equal to $1 billion would be reasonable if not conservative.

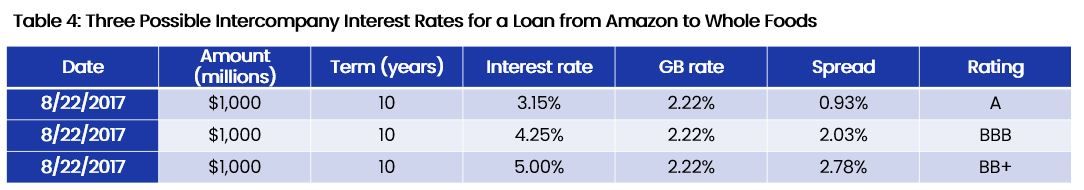

The

other question is what should be the intercompany interest rate. Table 4

considers a 10-year intercompany loan of $1 billion issued on August 22, 2017

with three possible interest rates. Which interest rate represents the arm’s

length standard depends on how one views the credit rating for the operating

affiliate. If Amazon’s group rating of A is used for the analysis, then the

arm’s length interest rate is the 3.15 percent third party rate paid by Amazon

on the same date for the same term to maturity.

If

Whole Food’s standalone credit rating of BB+ was seen as appropriate, then the

December 3, 2015 third party loan might be seen as the appropriate comparable

with one comparability caveat. Interest rates were slightly lower as of August

22, 2017 than they were as of December 3, 2015. Table 4 suggests that a 5

percent interest is consistent with a BB+ standalone credit rating.

Recent court decisions in other nations have

suggest an intermediate position between using the group credit rating versus

the stand alone credit rating. When the parent has a better credit rating than

the borrowing affiliate, the implicit support controversy suggests that the

appropriate credit rating be seen as stronger than the standalone credit rating

but not as strong as the group rating. If the appropriate credit rating were

BBB, then a credit spread near 2 percent would be appropriate. Table 4 reflects

this intermediate view as a 4.25 percent intercompany interest rate under the

arm’s length standard.

III. Concluding Remarks

We illustrated certain issues

that require addressing in any intercompany debt push down tax planning. The

first question is how much of the holding affiliate’s third party debt should

be allocated to any particular operating affiliate. The OECD’s Action 4 of the

Base Erosion and Profit Shifting effects on “Limitations of Interest

Deductions” offers guidance which state tax authorities might consider.

The other issue involves the

appropriate intercompany interest rate under the arm’s length model. We have

offered an economic approach consistent with the OECD’s recent “Transfer Pricing Guidance on Financial Transactions”. Our economic

approach focuses on the terms of the intercompany agreement (date of loan and term

to maturity) and the credit rating of the borrowing affiliates.

To contact the author of the post, click here.

_________________________________________________

[1] “Calculating Credit Spreads During A Pandemic”, LAW 360, April 27, 2020; “Translating Credit Ratings into Credit Spreads in Intercompany Financing, RoyaltyStat Blog.

[2] "Corporate Bond Spreads and the Pandemic," On the Economy Blog, April 9, 2020.

[1] “Calculating Credit Spreads During A Pandemic”, LAW 360, April 27, 2020; “Translating Credit Ratings into Credit Spreads in Intercompany Financing, RoyaltyStat Blog.

[2] "Corporate Bond Spreads and the Pandemic," On the Economy Blog, April 9, 2020.

For more details about the textbook and the course, contact us:

We are an online educational platform that helps professionals and aspiring individuals to succeed in their goals.

Featured links

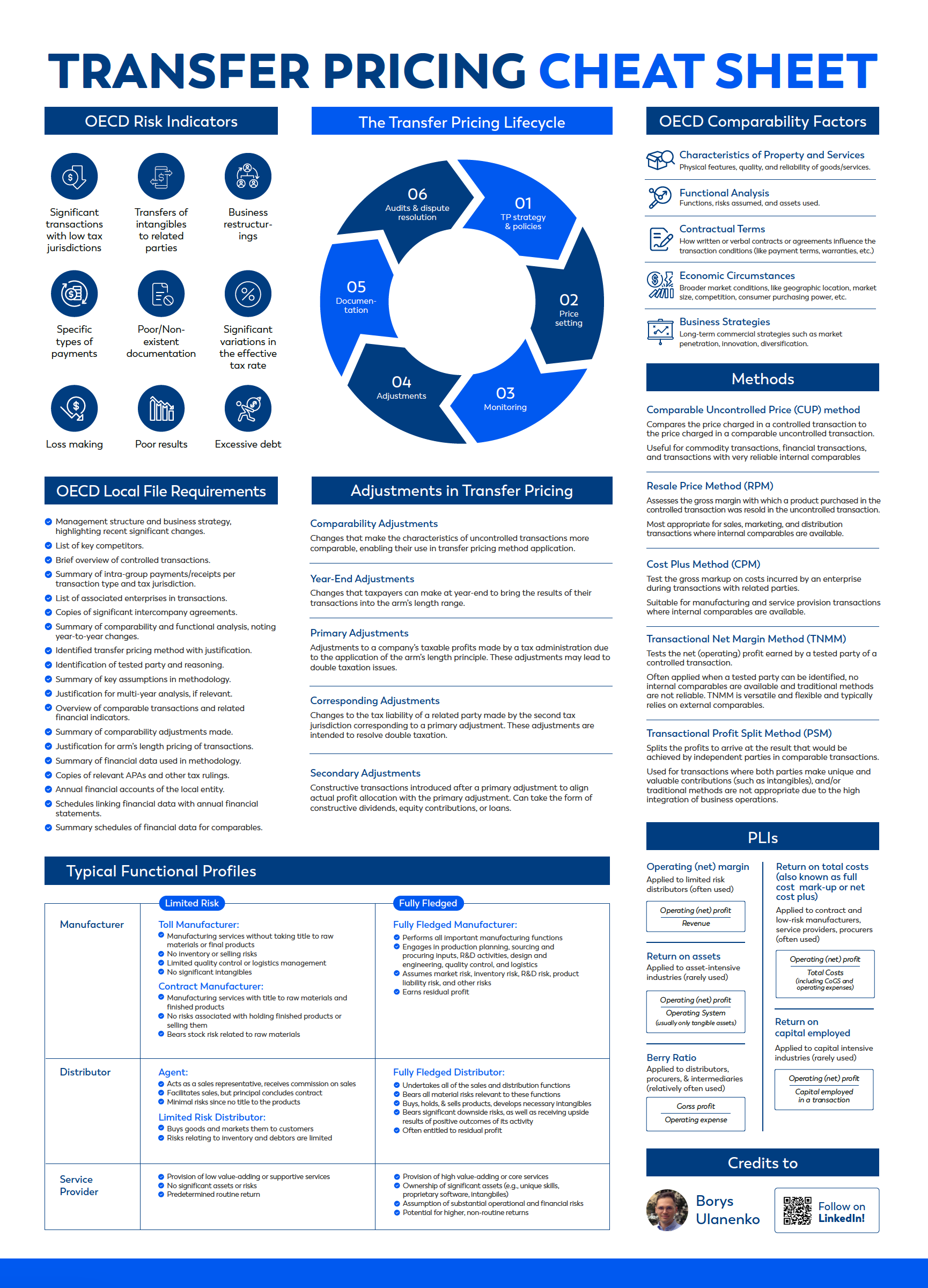

Get your free TP cheat sheet!

Discover the essential concepts of TP in one concise, easy-to-follow cheat sheet.

Thank you! Download here.

What is the EU Directive?

The EU is run by an elected EU Parliament and an appointed European Council. The European Parliament approves EU law, which is implemented through EU Directives drafted by the Commission. National governments are then responsible for implementing the Directive into their national laws. In other words, EU Directives are draft laws that then get passed by national governments and then implemented by institutions within the member states.

What is CbCR?

Country-by-Country Reporting (CbCR) is part of mandatory tax reporting for large multinationals. MNEs with combined revenue of 750 million euros (or more) have to provide an annual return called the CbC report, which breaks down key elements of the financial statements by jurisdiction. A CbC report provides local tax authorities visibility to revenue, income, tax paid and accrued, employment, capital, retained earnings, tangible assets and activities. CbCR was implemented in 2016 globally.